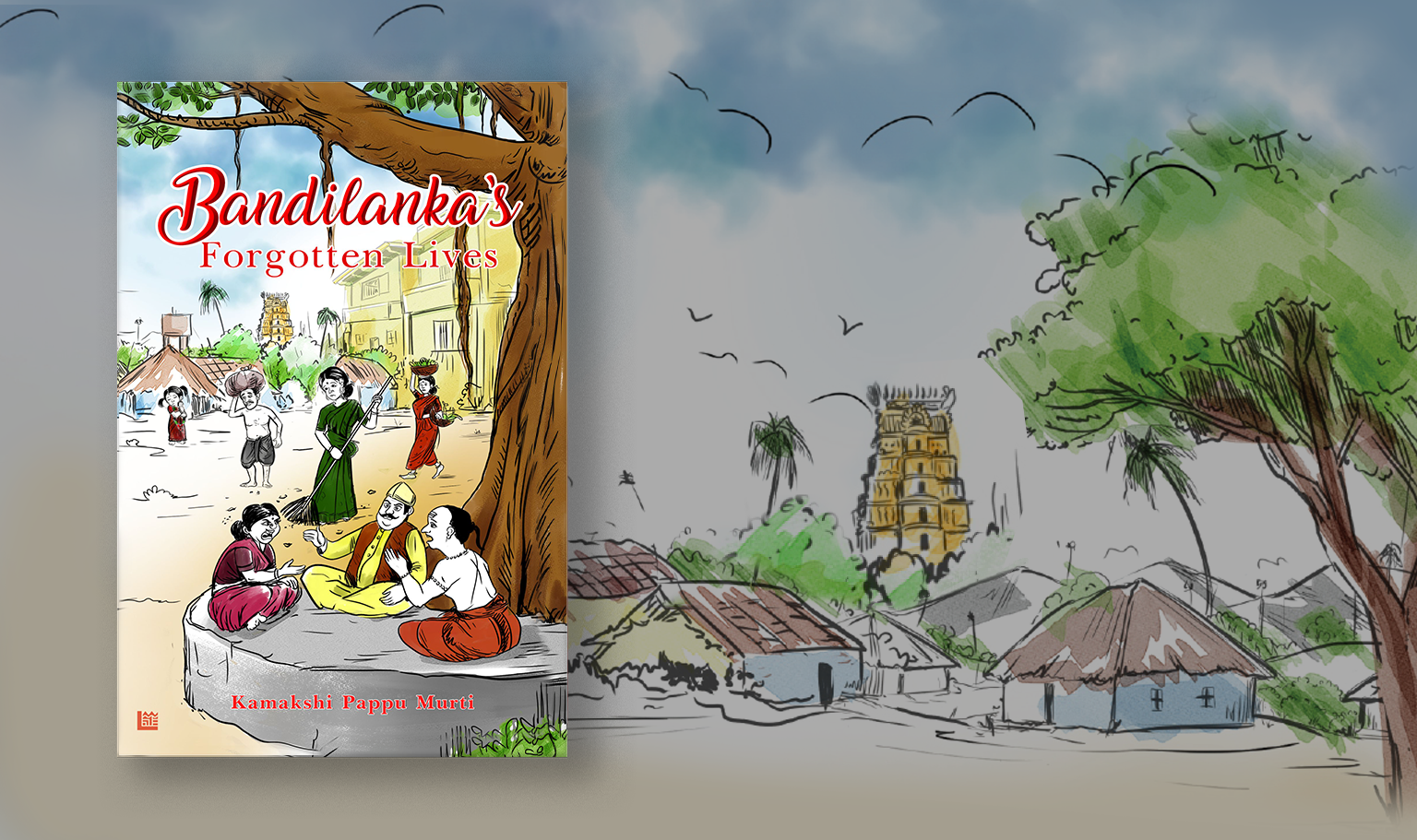

Forgotten Lives – A child widow, a Muslim migrant, a trans-person, a night-soil worker –

each bound by the common destiny of an invisible existence in human society.

“Bandilanka’s Forgotten Lives”: who are these forgotten people, and why is it important to shed

light on them, to return to them their stolen voices?

The summers I spent as a child in my maternal grandparents’ home in a remote village in

Andhra Pradesh, left memories of the family, of the food that my overworked grandmother

provided, of games I played with my cousins. What I didn’t remember or acknowledge were

those shadowy beings at the periphery of my childhood memory, those who slaved for us, and

starved, and slipped through the cracks: the overworked washerman, the abused female

sweeper, the nightsoil remover fated to die in the fetid fumes of the sewers, the beggar lying in

the mud, the widow disgraced for daring to outlive her husband, the LGBTQ+ derided for daring

to transgress so-called traditional norms … what if I were to flesh them out, to listen to their

concerns?

My stories will hopefully attract those of you who are not only interested in learning about

other cultures, but also willing to critique their own. I have attached one of the stories, hoping

you, my reader, will judge for yourself the significance of these lives, and to honor them for

their unrewarded labor.

*****

“A widow reborn”

Small-pox was ravaging Bandilanka. The grounds were covered with bodies waiting to be

cremated.

“Send the untreatable cases home!” the local doctor directed the two nurses on call.

“There is no room for them here.”

Venkateshwara Rao whispered:

“Just one glimpse – one glimpse of our daughter!”

Gayatri shook her head.

“The doctor says it is too dangerous – the infection.”

Venkateshwara Rao tried to nod. The sores were rapidly closing his eyes. He could make out the

faint form of his wife.

“From the door, perhaps?” he whispered again, every word hurting his throat.

Gayatri ran into the next room and returned with a tiny bundle in her arms.

“May God bless and keep you, my daughter,” he murmured. His eyes closed. The room became

very still. Gayatri bent her head as her tears bathed the tiny body of daughter Sarada.

“Come, daughter!” Her father’s voice softly brought her back to the unforgiving path of

the living. Your mother-in-law wants to see you.”

She drew back. What would the in-laws think? That it was her fault? That it was because

of her sins from a previous birth? She felt the baby in her arms – sound asleep. Would they,

would she want to take her child away?

She stepped into the drawing room, followed by her father. The father-in-law was sitting

in the most comfortable armchair. His wife stood behind him like a sentinel.

“Brother-in-law,” she heard him address her father, “Once the cremation is over, we will

return to Guntur – with our daughter-in-law.”

The mother-in-law stepped out from behind the armchair.

“You need not bring anything for yourself. Just get the child’s clothes and anything else

you need for her.”

“Yes, Atha,” Gayatri murmured, keeping her eyes lowered to the floor. Why doesn’t she

look at my child, at her granddaughter? Does she think this innocent child is responsible for her

father’s death? Baby Sarada opened her eyes as if sensing her mother’s distress. She pushed

her mouth against her mother’s breast, and made loud sucking sounds.

“If you will excuse me, Atha, I have to …”

“Yes, yes,” the mother-in-law said impatiently. “Go!”

She sat on the cot, released the buttons on her wet blouse, and felt her child’s mouth

unerringly find the nipple. The tears from her eyes mingled with the milk that fed Sarada. A

little later she lovingly placed the sleeping child in the cradle. As she straightened up, she felt

her father’s hand on her shoulder.

“Gayatri! Listen to me, daughter!”

“Nanna! What if … what if … “

“That is what I have come to tell you. I will not allow them to take you away, Gayatri.

We, your mother and I, have decided …”

She said, disbelief tingeing her voice:

“Can you do that? Can you really do that?”

“Tradition might dictate otherwise, daughter. But a tradition that tells us that a

daughter is less important than a son needs to be questioned.”

Gayatri stared at her father. He never ceased to astonish her.

“What if the in-laws create trouble? I don’t want to …”

Her father sat down and sighed.

“And here I thought you wanted to study, to educate yourself, to make something of

yourself. Of course, if you wish to go to Guntur and live the life of a widow, we cannot prevent

…”

“No, no, Nanna!” she interrupted. “Of course not! My husband – your son – and I talked

about it often. He wanted me to go back to college.”

“Well then, we will only be following his wishes.”

*****

Kamakshi Pappu Murti is a retired professor of German Studies. She has authored fictional and

non-fictional writing. Her scholarly writing is devoted to multi-cultural issues, as well as gender

studies. Murti is an active member of the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators

(SCBWI), Women’s Fiction Writers Association (WFWA), Modern Language Association (MLA),

American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL), and the National Conference

on Race and Ethnicity in American Higher Education (NCORE).